During the month of February, I will be teaching a class at Fellowship Congregational UCC- Tulsa on the Book of Revelation. I’ll be sharing the videos of those classes, and supplemental materials, here. Last Sunday, the 2nd, was the first class, but unfortunately, we had a tech issue and the class didn’t get recorded. So, here is the full text of the script I wrote for the class (which I’d say I about 30% stuck to), as well as my slides, interspersed throughout.

My favorite place to start with any class like this is hearing from y’all. What are you impressions, experiences, or opinions about the book of Revelation? How many of y’all have read it? Did anyone grow up in a context where it was presented as an “end of the world” blueprint?

I think one of the most important things we can do in this class, as well as one of the most difficult, is recognize what it is we are bringing to our study of Revelation. Few books of the Bible come laden with as much baggage as it does, and I think this is largely because it is so hard to understand. So we layer on top of it all these things we were told or taught, in order to try to grasp onto something. And so, I don’t want us to jettison all that stuff, because its part of who we are. But, I don’t want that stuff to get in the way of a new reading Revelation either. I want everyone here to try to be as open to Revelation as possible, to see the possibility of reclaiming it, in a way, as a text that can inform our priorities as a church and as a people.

So, in order to do that, I think we need to start today with two goals in mind: getting the facts straight on the book of Revelation, and thinking about a hermeneutic strategy for reading it; or, in other ways, making a decision on how Revelation should be interpreted. Those are the two main things we do today; because of that, we aren’t going to dive deep into in the content of Revelation just yet, all the weird images and creatures and such. That will come over the course of the next three weeks. Today is more a 30,000 foot view.

So, let’s start here: Revelation fact sheet. A few basic things, which we will unpack in more detail. First, it was written by a man named John, who was writing on the Greek island of Patmos. It was written in the second half of the first century, likely around 90 CE, so about 50 or 60 years or so after Jesus’ death, and probably about 30-40 years after Paul’s letters and the writing of the Gospels. It is most likely the “newest” book in the Bible. It was written as a circular letter to churches in Asia Minor, and specifically seven churches that are named in the first couple of chapters. And finally, Revelation is the most well known example of a genre of ancient writing known to us as “apocalyptic literature.”

Ok, let’s drill into these. First, who was John? Well, we don’t really know very much about him, beyond what he tells us in the text, and what a few early Christian writers claimed. We can feel pretty certain that he was Jewish, and some literary clues point to him being from Palestine originally. Since he’s writing to churches in Asia Minor with some detail, we can surmise he was preaching or pastoring churches there. And, he tells us he was on the island of Patmos when he wrote Revelation, and alludes to perhaps an imprisonment there, or exile. Briefly, here is a map, where you can see Patmos, in relation to Greece. And, as I mentioned above, Revelation is written to seven churches in Asia Minor, all of which are in this general vicinity.

One thing we can say, that is pretty important, is that the John who wrote Revelation is almost certainly not the John who wrote the Gospel of John, or the Epistles of John. There are significant stylistic differences in the original texts, between the Gospel, the Epistles, and Revelation, that make it hard to argue that these were all authored by one voice. Instead, many scholars posit a Johannine community from which all these texts arose. This community was likely centered around a specific location, or figure associated with the early Jesus movement, from a which a unique take on the faith – influenced by Gnosticism and other forms of Jewish mysticism, and leaning on the Spirit of God as of primary importance – arose. This community is distinct in its emphases from that which birthed the Synoptic Gospels, as well as the Pauline epistles and other New Testament works.

The next question to answer: what was happening when John wrote the Book of Revelation? Well, if we accept that it was written around 90 CE, then we know that a man named Domitian was the emperor of the Roman empire. Domitian is not thought of as a very good emperor today, although some newer takes on this era have tried to paint him in a different light than he historically has been. Whatever his personal foibles, it is unavoidable that there was widespread persecution of Christians and Jews during his reign. This included widespread violence between Christians, Jews and pagans in Asia Minor, the area to which John was writing.

The primary thing which early Christianity and Judaism were still grappling at this point in time was the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem twenty years earlier. Domition’s father, the emperor Titus, and his brother the emperor Vespasian led the campaigns that resulted in this, and the end of an semi-independent Israel. It’s hard to describe how momentous of an event this was. It can plausibly be argued that Christianity owes its very existence as a movement that spread to the destruction of the Temple in 70, and the shockwaves that sent through Jewish communities across the ancient Near East. The destruction of the Temple shook people’s conceptions of what the religion even was, and likely pushed people towards sects that offered a different vision of hope and the world to come.

What we can say unequivocally is that John and his community were still grappling with this event, and what it meant for their faith. Another factor we can see reflected in the text is the long shadow of the emperor Nero, who despite dying almost half a century earlier, still was very much on people’s minds in the Roman empire. In fact, a common belief among some groups – Christians very much included – was that Nero hadn’t in fact died in 54 by his own hand, but had gone into hiding, and was biding his time to return and reclaim the throne. Although by 90 CE, the hard facts of chronological time stretched the bounds of credulity, the looming specter of a “reborn” Nero coming back to institute a reign of chaos and terror was ingrained in many people’s minds.

So, knowing now a little bit about the author, and the context, of Revelation, let’s explore what we mean when we call Revelation an “apocalypse.” Apocalypse has a different meaning today than it originally did. We think of apocalypse today as a story about the end of the world, particularly stories that include violence or dystopian elements, or which end in disaster for humanity. But, apocalypse in the classical sense is actually a genre, specific to Judaism during and after the Second Temple period. The Greek work from which we derive our work apocalypse actually has meanings closer to “unveiling” or “revealing”, rather than anything specifically to do with the end times. Apocalypses certainly included visions of the future, and even of the end times, but they were not predictions, there were not considered prophecy (especially not in the Biblical sense) and they didn’t all involve disaster or cataclysm. Revelation is not the only apocalypse included in Scripture; Daniel and Ezekiel are both considered apocalypse, as are the semi-canonical texts 4 Ezra and 1 Enoch.

An apocalypse is meant to reveal truths about the world around the reader, that otherwise would not be known or understood. Apocalypses take images we are familiar with, and turns them around and inside out, to reveal all new realities.

The New Interpreters Bible says a couple of things about apocalypses that I find really helpful; first, “an apocalypse by nature both expands and overturns our expectations.”

And, “Apocalyptic imagery beckons us to suspend our pragmatism and to enter into its imaginative world.” So, apocalyptic literature, at its core, is trying to get us to see things differently than we might otherwise. It takes our expectations and our presumptions and what we are comfortable with, and makes it jarring and new and distinctly uncomfortable.

And, so before we talk about the content of Revelation itself, this is a key thing I want you to hold onto over the next three weeks of this class: let down your guard with Revelation. Lean into its weirdness, and the discomfort some of the imagery causes, and let go of what you think you already know or feel about it, and try to see something new, try to have fresh eyes, so that we can find out what this book is trying to communicate to us.

Ok, now the elephant in the room: what is actually in Revelation? That’s a question with a really big answer. There is a lot packed into the 22 chapters of Revelation. Now, we could spend four weeks here going through this book chapter by chapter, and trying to highlight images here and there and imagine what they are. But, frankly, I don’t think that’s a good use of our time, nor is it the best way to approach Revelation. So, let me state it here: we are not going to touch on a lot of the stuff in Revelation, not in this class. We’re going to take more of a 30,000 foot view of it, and actually try to learn how to read it, so that you can go do that.

So, here is a very, very brief outline of Revelation. I’ve split the book into three parts: first, chapters 1-5 are a sort of introduction to the book. We get John’s intro of himself, then we get seven short letters written to seven different churches in Asia Minor, then an opening vision, of God’s heavenly court.

Next, in chapters 6-16, we get the meat of Revelation, the chapters with all the creatures and violence and everything you may be most familiar with. These are the chapters where we get 3 sets of 7 Divine Judgements, described as the Seven Seals, the Seven Trumpets and the Seven Bowls, and woven into those, are Seven Signs. Seven, as you can tell, is an important number for John, and for Judaism in general. Seven represents the seven days of creation, and thus can be understood as pointing to completeness, or perfection even. Seven is considered to be the holy number of God, and in these visions of God’s judgement, John sees sevens everywhere.

Finally, chapters 17-22 conclude Revelation by describing the so-called Battle of Armageddon, where the Beast and Dragon are defeated, and then God’s eternal Kingdom arrives, and is described in great detail.

If you look at the handout I gave you, you will find a one page visual outline of Revelation, from the Bible Project. Now, this is a really busy image; there’s a lot happening here, and we’re not going to try to go through it in detail. I’d encourage you to take it, and peruse it at your leisure, perhaps while reading Revelation itself. Also, if you Google the Bible Project, they have a series of videos on Youtube that illustrate these images and outline the entire book. I don’t always agree with every theological choice they make, but the Bible outline images and videos are really well done and super informative if you want to just get a broad outline of any of the books of the Bible.

Revelation is not a straight forward book to read. It is not a narrative that you can sit down with like a fairy tale. It’s an apocalypse, a series of visions, requiring interpretation and contemplation. People have understood this for a long time, and over the course of time, there have come to be four main interpretive strategies folks have employed for reading Revelation. Let’s run through these really quick.

First, the way of reading Revelation that most people are familiar with is as a straightforward account of the end of history. This is the type of reading where the reader looks at Revelation as revealing how the end of the world will happen, and then proceeds to try to imagine how all those signs and seals and bowls and creatures will manifest here, in our world.

For the record, my position is, don’t read Revelation like this. It’s a bad way to read apocalypse.

Second, there is the purely historical reading, wherein one approaches Revelation as applying solely to the first century context in which it was written. This is not a bad strategy at all, obviously, and is an important piece in any interpretive strategy. Trying to discern what John was imagining and referring to is close to impossible, as reading someone’s mind two thousand years on tends to be, but scholars can and do make a series of inferences that can guide readers about what it going on.

Third is the contemplative or mystical reading of Revelation, where the reader understands the images as a description of the souls journey towards God. I don’t wholly recommend this reading, but I also don’t wholly discourage it. There is definitely worth in much of Scripture for reading it with personal growth and development in mind, and even Revelation can serve that task. But, there is definitely a lot more going on here.

Finally, the fourth strategy is similar to strategy two, but instead of applying Revelation just to the first century, some readers try to apply it to other periods of history, or even the whole sweep of history since the life of Jesus. Now, this strategy certainly has its dangers and its pitfalls. But, it can also be useful to try to discern the happenings of the world around us by turning to the images and signs of Revelation, as a way of reimagining our world, and from there, maybe beginning to see new solutions and ways of being human. When we get to weeks three and four of this class, this is actually the strategy we will come closest to.

Now, we are all aware of that Revelation has proven very problematic through history, and especially recent history here in the US. Revelation has been twisted into a text imagining a violent and angry God, ready to rain down death and judgement on a sinful humanity, with a small remnant of believers coming through the hellscape and inheriting the kingdom of Revelation 22. You could literally design an entire semester long course around unpacking the various ways Revelation has been read just over the last century in the United States. I’m going to try to broach it in about 2 minutes here, so bear with me.

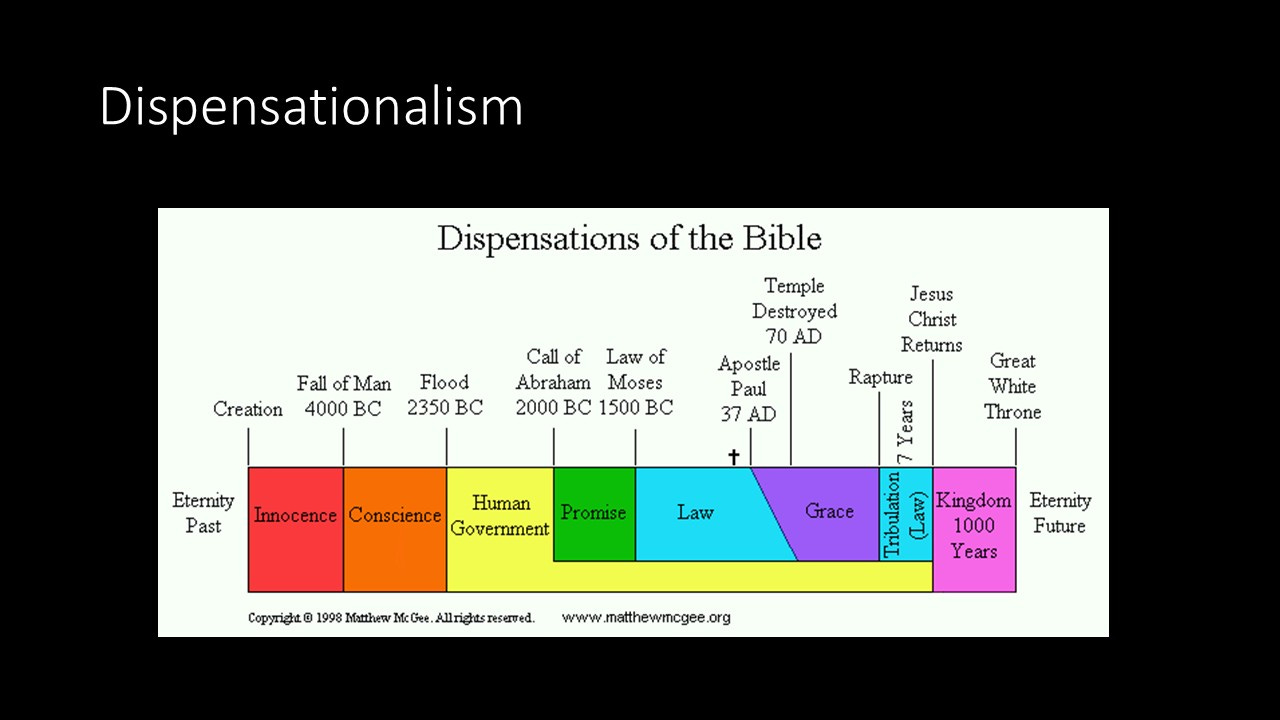

Revelation, in the first decades of the twentieth century, became a key text for fundamentalist Christians, the capstone of a literalist reading of Scripture that posits Revelation as the final historical tale in a history text. A lot of this can be laid at the feet of this man, Cyrus Scofield, who in 1909 issued his Scofield Reference Bible, which introduced the concept of dispensationalism to American Christians.

In short, dispensationalism holds that history can be divided into a series of dispensations, or eras, starting with Creation, through the story of the Old Testament, up to Jesus, and then the two thousand years since, which are classified as the Dispensation of Grace. Scofield argued that the next dispensation would come after the Rapture, an idea invented in the 1830s by misreading a single verse in 1 Thessalonians, which would usher in the beginning of the Tribulation Dispensation that he said was described in Revelation. After the events of this dispensation would come the final dispensation, the Millenium, or the 1000 year reign of Christ on Earth, before the final defeat of Satan, and beginning of eternity.

This, of course, is the understanding of Revelation that drove the immensely popular Left Behind books in the Nineties. Did anyone here read those? I admit I did, multiple times, voraciously. For all the problems – and there are so many problems – they are exciting, gripping tales. And this is where they come from.

Now, from dispensationalism, we get another series of Revelation interpretations, grouped together under the title of Millenarianism. Basically, these four ideas - Amillennialism, Post-Millenialism, Post-Tribulational Pre-Millenialism, and Pre-Tributional (Dispensational) Pre-Millenialism – are disagreements about when exactly the Millenium, that final dispensation when Christ reigns, will occur. We are not going to get into the differences of these; if you want this chart, I can get it to you. But, we can safely summarize all of these as really damaging literalist readings of Revelation that cause people to spend hours arguing over things that really just aren’t that important. But I digress.

So, I want to close with this question: Why should we read Revelation? After all, as we’ve discussed, Revelation is weird, and confusing, and probably outdated, and has been used to perpetuate a lot of damaging theology and ideologies. Why bother? Isn’t there a lot of other good stuff in the Bible we could spend our time on?

These are fair questions, and I certainly empathize with that attitude. But, I’m not a fan of ceding entire swathes of the Bible to fundamentalists. It’s why I did the Paul class last year too. This is our Bible, as much as it is theirs, and we can reclaim texts like Revelation to help us get a better understanding of the love and the mercy and the justice that Jesus taught and lived.

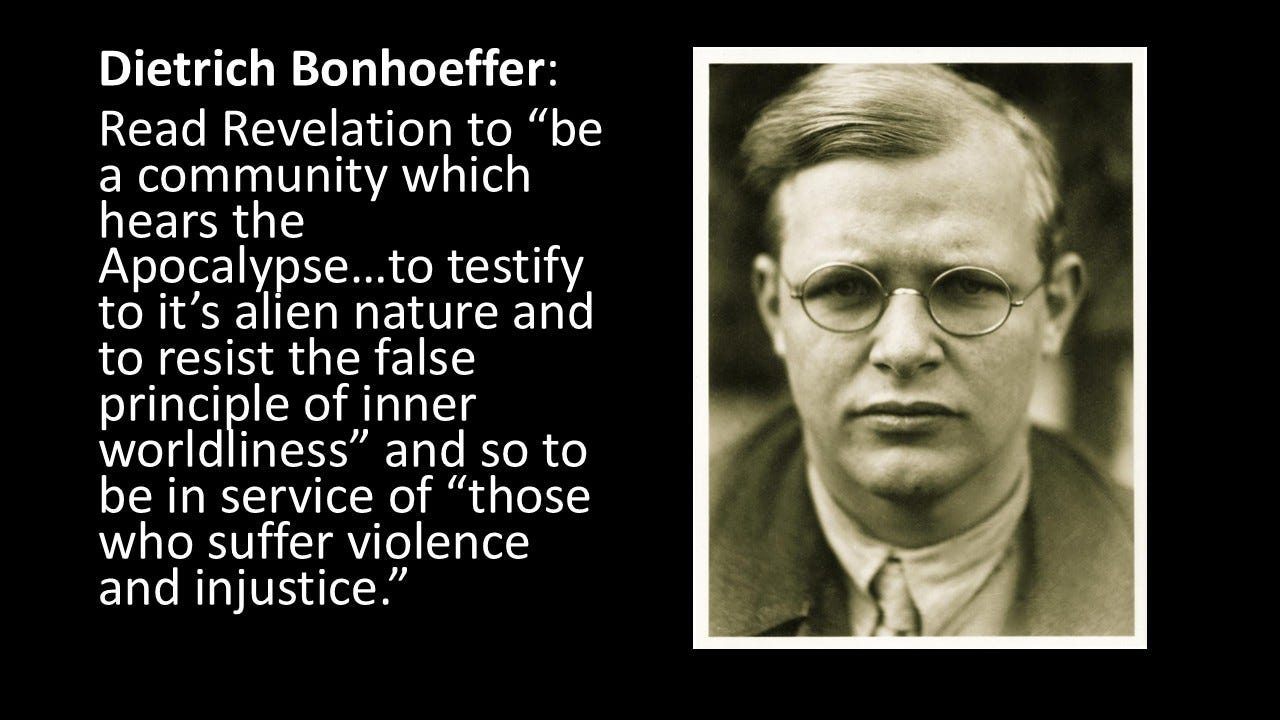

So, let’s turn to one of my favorite Christians, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, for help answer this question. For those who don’t know, Bonhoeffer was a German theologian in the first half of the twentieth century, who was a pacifist, but who signed onto a plot to kill Hitler. It was found out, he was imprisoned, and then killed by the Nazis just days before he was to be liberated. Bonhoeffer wrote an entire book on Revelation, and he told his readers to read Revelation in order to “be a community which hears the Apocalypse…to testify to it’s alien nature and to resist the false principle of inner worldliness” and so to be in service of “those who suffer violence and injustice.” I know that quote can be a little hard to track, but what Bonhoeffer is instructing here is that Christian communities of peace should read Revelation as a call to act with justice. Bonhoeffer saw Revelation as a book that envisioned a new way of confronting the tyrants and the violence of the world, but the turning upside down of history by the Conquering Lamb of God.

As we talked about earlier, Revelation can be a hard and uncomfortable book to read. The images challenge us. But, turning to the NIB again, the writers remind is that often, “we are resistant to a text that confronts our particular interests and the power structures in which we are so deeply implicated.” As we will see, especially in week three, Revelation can actually be understood a critique of all structures of power and domination and control, and as people who certainly benefit from those structures in many ways, we can get some unease as we sense the critique at work under the images and signs.

It can also be tempting to dismiss Revelation because its weirdness, because we feel that it is irrational or unimportant in a civilized, modern world. The NIB also chides this impulse in us, saying “We must avoid treating texts as a problem that we as enlightened, modern interpreters can solve.” This is a reminder to let the text stand on its own, and to read it on its terms. It is telling us something, if only we can allow ourselves to hear it.

Finally, I love this quote: “Revelation is a classic example of art that stimulates rather than prescribes.” This is, I think, a really important reminder for us progressives. We like the parts of the Bible that feel like ethical instructions for living in a unjust world: “love your neighbor”; “remember the poor”; “welcome the stranger” “give up your wealth.” I like those verses. But, sometimes Scripture is not about telling us what to do. Sometimes, Scripture is trying to get us to see the world in a whole new and different way. This is a complement to those prescribing verses; we may think we know what it means to remember the poor, but as my favorite theologian Stanley Hauerwas likes to remind us over and over in his books, we have no idea what it means to remember the poor or love the neighbor until we begin to see the world like Jesus saw it. Maybe that’s what Revelation is trying to do: get us to see things anew, so that we may be better disciples.

To that end, I want to end by going to one of the best books on Revelation I’ve read, Upside Down Apocalypse by Jeremy Duncan. In it, Duncan introduces this idea of “subversive storytelling.” The idea is that Revelation is doing what Jesus did with his parables and some of his actions: using story as a way to subvert the powers and the expectations of the world. Duncan writes, (quote slide 20.)

Duncan, at this point in the book, had been talking about how many apocalypses, then and now, centered on revenge. Apocalypses use strange imagery to hide the desired outcomes of the world from those in power, because so often the desired outcome in the face of tyranny and oppression is to get even. But, Duncan argues, Revelation isn’t about revenge. Revelation sets up all this violent imagery, inflating the readers expectation that God is about to get even with God’s enemies….and then instead, John knocks that all down, by centering in again and again on slain Lamb on the throne of God, ruling through submission and love rather than violence and fear.

Here is Duncan, on the effect John’s subversive storytelling has. This is the essence of Revelation, right here. John is telling a different, weird, backward, illogical story. And he’s doing it because that’s the only way to undo the threads of empire that are all around us, and to begin see the world in a new way. Jesus did this so often. John gets that, and he does that too, right here in Revelation.

Which presents us with this question, which will stick with us through this whole class: what happens when we read Revelation, not with the Rapture or Left Behind or dispensationalism or whatever in mind, but with Jesus in mind? How does that change what we find here? That’s what we’ll see.

So, next week, we are going to focus on violence in Scripture, because Revelation is full of violent imagery, and we are going to think about how to handle violence in the Bible. From there, we’ll be able to move on in weeks three and four to new ways of reading Revelation, centered around nonviolence and resisting empire in new and creative ways.

But, we will also have time next week to explore some of the weirdness of Revelation. For next week, you have a task: read Revelation. All of it. That sounds daunting. It’s not. Revelation is actually relatively short. In my Study Bible, it takes up all of about 25 pages, half of which are notes on the text. It’s a short read. Read it with the Bible Project outline, and with pencil and paper. Notate it. Mark it up. Write down questions you have. We’ll be able to spend time on those questions next week.